New Ransomware Reporting Requirements Kick in as Victims Increasingly Avoid Paying

As the year turns, and weary defenders begin to worry about what new threats will present themselves in 2024, the conversation of ransomware payment bans has resurfaced. This is not a new debate and resurfaces from time to time, so we decided to unpack this issue.

Why would a country consider a ban?

The rational answer to this question is that a government would enact a ban because they truly believe the policy would minimize ransomware payments and compel cybercriminals to cease attacking organizations within that country. This also implies that every other policy tool, from federal regulations to industry-specific rules and guidance, was exhausted and proven ineffective. The explicit message would be: we cannot get secure by any other means.

What would a sovereign ban signal?

Capitulation, in short. A ban would signal that as a country, we are admitting that we are incapable of defending ourselves. That we are helpless against the threat of cyber extortion. Some advocates for a ban truly believe US companies and organizations should give up trying, with messages such as,: “The reality is that we’re not going to defend our way out of this situation, and we’re not going to police our way out of it either.” We respectfully disagree.

We have seen change happening first hand over the past few years. Enterprises are no longer getting completely crippled by encryption attacks with the frequency they were in 2019. Law enforcement agencies are doing meaningful work to disrupt and dismantle ransomware groups in ways that impose real costs on the threat actor organizations. This fight will not be won overnight. It will take years, but the fight IS winnable.

But could a ban work, is there precedent?

Early experiments have been ineffective, but most sovereign nations that have seriously considered a ban have opted to continue fighting instead. Several US states have enacted ransom payment bans on state agencies or organizations. But, while Florida and several other states have imposed these regulations, we have not yet seen a decline in attacks inside these states.

From a sovereign nation perspective, Australia probably had the best chance of seeing some success from a national ban. The attributes of Australia that are unique and give the country the best chance of success are:

1) The country is relatively small compared to the US (the US absorbs the largest percentage of attacks globally), so in theory, if ALL cybercriminals gave up on attacking Australia, the cyber crime addressable market of targets would not shrink too much.

2) They have a functional government capable of enacting new laws quickly. The US….eh, struggles with this…from time to time.

3) On the heels of several high profile incidents that impacted large proportions of the population, there is likely strong public support for such an initiative.

But, even with these favorable characteristics, the Australian government, after careful study opted to enact substantially more stringent reporting requirements, and made large investments in law enforcement and prevention. In short, again, they decided not to waive the white flag and dug into the fight.

How come cybercriminals keep attacking organizations located in states with a ban?

Two reasons:

1) Cyber criminals have more experience dealing with ransom payment decision making than all of us, including federal policy makers. They know that victim organizations will try to work around the rules when necessary, and the cybercriminals are happy to introduce shady service providers who turn a blind eye for a buck or two.

2) It is very often the case that the threat actors don’t bother to research where a victim is located before attacking them. Even if they know a victim is located in a state with a ban, they won’t bother to discern if the victim is a state organization or not.

Humor us, what WOULD happen if the US enacted a national ban on ransom payments?

Two things would happen immediately.

1) A very large illegal market would be spawned overnight to service ransomware victims that needed to pay.

2) Much of the progress made on government / agency reporting would be reversed overnight. Victim reporting would drop dramatically and victim cooperation with law enforcement that contributes to their ongoing disruption efforts would dissipate dramatically.

Why would an illegal market be spawned if ransom payments were banned?

Demand. There would still be demand for ransom payment services because people and organizations will do what they must to survive. The Brookings Institution answered this best:

“When someone is in a desperate situation, banning their only way out of that situation doesn’t stop them from using it; it only makes the cost of doing so higher and the victim more vulnerable. Banning unauthorized migration doesn’t stop migration. It just guarantees that the only service providers for those desperate people have no check on their ability to victimize without impunity. If banning economic behavior that is required for survival worked, then there would be no drug trade or [illegal] market for human organs.”

Another reason is precedent. When we started Coveware, there were two highly prevalent activities occurring that compelled us to found the company. First, there was a proliferation of ‘data recovery companies’ that would prey on unsuspecting ransomware victims. They would claim to be able to crack the encryption, when in reality they were just paying the cyber criminals. Several are still operating today. A national ban would be a goldrush for companies like this and others that would rush into this new illegal market (Coveware would not). Second, enterprises would just start building contingency plans outside the US. Another trend we noticed back in 2018 was the prevalence of large enterprises that were setting up entities in the Caymans or other jurisdictions just in case they had to deal with a ransom payment. As legitimate best practices have taken root over the past few years, offshore contingency planning by enterprises has diminished. A national ban would push enterprises to spin up offshore contingency plans overnight.

You are exaggerating…clearly no rational company would KNOWINGLY break the law and use an illegal service provider to pay a ransom, right?

Wrong. A substantial proportion of these victims would do the quick math on the risk (company badly damaged, vs. risk of fines and penalties), and then proceed to navigate the illegal market of service providers. We still see this behavior regularly today, so we don’t expect it to change in the future.

Why would companies stop reporting if ransom payments were banned?

Some companies would still report to be sure, but any victim that even contemplated paying or chose to pay would absolutely keep it quiet as they would be admitting to a crime if they reported. This is such a concern that the FBI has stated publicly that:

“If we ban ransom payments now, you’re putting US companies in a position to face yet another extortion, which is being blackmailed for paying the ransom and not sharing that with authorities,”

But does mandatory reporting actually work? Do companies actually follow these rules or guidelines? What is the benefit?

Absolutely. Here are a few examples.

In 2021, the U.S. Treasury issued guidelines that laid out the diligence and reporting requirements that victims of ransomware should follow, and stated that following these guidelines may offer relief from liability. Prior to this guidance, formal diligence on who the threat actor was, and if there were any sanctions issues was NOT considered regular best practice. Since these guidelines have been released, completing thorough diligence prior to any payment has become normal best practice within the incident response industry. Reporting was also not regular best practice prior to the 2021 guidelines. After the release of the guidelines, reporting became standard practice overnight. The US Treasury guidelines sparked an INCREASE in reporting to law enforcement which is good. They also created a diligence framework and standard for how victims could avoid paying a sanctioned actor. Both are positive.

In 2023, NYDFS issued new guidelines that require detailed disclosure from covered entities on the facts and circumstances of a ransom payment. If a covered entity fails to follow these guidelines they can get fined, or worse, lose their ability to operate in New York (a pretty important State to operate in if you are in financial services). These guidelines increase the volume of information NYDFS is receiving about the nature and type of threats facing covered entities. The specifics of the reporting also force covered entities to develop their own framework for decision making when facing cyber extortion, as they will have to explain their rationale for paying a ransom to NYDFS in their report. This is also positive as it compels the covered entity to perform IR planning ahead of an incident and more rigorously consider their decision.

A ransom ban cuts the flow of money; it is as simple as that, right?

Academically speaking, yes. Practically speaking, no, it will just re-order the flow of money through a new illegal market of service providers. A ban will also NOT create an incentive for executives to increase security spending as some argue. Why? Because the amount of security spending necessary to effectively eliminate ransomware risk is so large, no executive team would be incentivized to authorize it. As the late Charlie Munger famously said, “you show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.” Executives with large stock holdings make decisions based on the perceived short term impact to the stock price of their company. Depressed profit margins hurt stock prices 100% of the time. A ransomware attack does not have a 100% chance of even happening.

You are obviously biased, Coveware’s entire business is dependent on ransom payments after all!

It may surprise some readers to learn that Coveware’s business is not dependent on ransom payments. The majority of our revenue comes from proactive products and services. Additionally within our incident response business (of which cyber extortion incidents are just a portion), the outcome of a cyber extortion event has no bearing on our revenue. From inception, we designed our business to ensure there was no financial incentive towards ransom payments. This allows us to give unbiased advice to clients that is purely predicated on the forecasted future outcome of their decision. This is also why we lean so heavily on the data reported herein showing that progress IS being made.

Well, the status quo is not working either so, what's your plan Coveware?

We could write another 5,000 words on this topic, but in short, greater costs must be imposed on the threat actors by changing the incentives of the victims. Carrots and sticks are necessary.

Carrots:

While the 2021 US Treasury guidance was very impactful in creating a baseline standard for reporting and due diligence, this framework could be taken even further. There is ample DOJ precedent for offering safe harbors in exchange for proactive reporting. In addition to certain mandatory reporting requirements (see sticks), Treasury or other regulatory bodies could define a safe harbor from enforcement action if the victims meet certain requirements over and above what is already outlined. Criteria to qualify for a safe harbor could include a more comprehensive definition of threat actor diligence performed prior to paying, a valid reason for the payment (i.e. ransom payments for undefined, non-tangible deliverables are not qualified), and a commitment collaboration with law enforcement over and above a simple filing. A major issue facing law enforcement is victim collaboration post incident. Any safe harbor considered should compel victims to collaborate with law enforcement on any and all reasonable requests, regardless of the request’s proximity to the date of the incident.

Sticks:

NYDFS has already enacted several regulations that we think will be helpful (especially section Section 500.17), but future guidelines could go even further to eliminate the availability of a safe harbor if the payment was made for reasons deemed unreasonable (such as paying to suppress publication of already stolen data). We do NOT support the type of sticks that impose personal liability upon CISOs or other executives. That is just going to drive talent away from these critical jobs and make companies less safe in the long run. It is enough to impose exorbitant fees upon offending companies for failures to disclose or notify. Scaring talent away is bad policy.

Imposition of costs:

Much of the support for a ban seems to radiate from a desire for a short term, quick fix. Indeed, a ban would probably create a quick drop in ransomware payments (note, not attacks, but payments). As described above, things get a bit more complicated longer term. There is no getting around the fact that imposing major costs against threat actors takes time. The recent DOJ actions taken against Binance are a great example. It has been long established that a substantial proportion of ransom payments were laundered via Binance. The US case against Binance goes back years (i.e., it was not quick, it took a long time). It will COST threat actors money to launder ransomware proceeds via less liquid exchanges now that Binance is theoretically not available to them.

The ability for law enforcement agencies to impose costs also depends heavily on victims being collaborative for long periods of time after the incident. Investigations take time. Within the active cases we handle, we would estimate that close to 100% of victims are doing some form of law enforcement notification at the time of incident, which is consistent with the 2021 US Treasury guidelines. We would estimate that less than 10% of those same victims, when contacted by law enforcement for further assistance in the months and years afterwards, actually continue to collaborate. This lack of follow through badly hamstrings law enforcement bodies as they can not bring investigations to a close without collecting proper evidence from victims. This is why reporting obligations need to be more clearly defined and incorporate the longer term needs of law enforcement.

Imposing material costs takes time. There is no getting around that. Over the years, we have proposed a substantial number of ideas to foreign sovereign governments, and various agencies in the US that would make paying ransoms materially more difficult. We stand by these ideas and despite the temptation to reach for the easy button, we feel the only way to ‘win’ is the hard way. The real question is do US policy makers recognize this, and share in our belief and spirit that we CAN win the hard way.

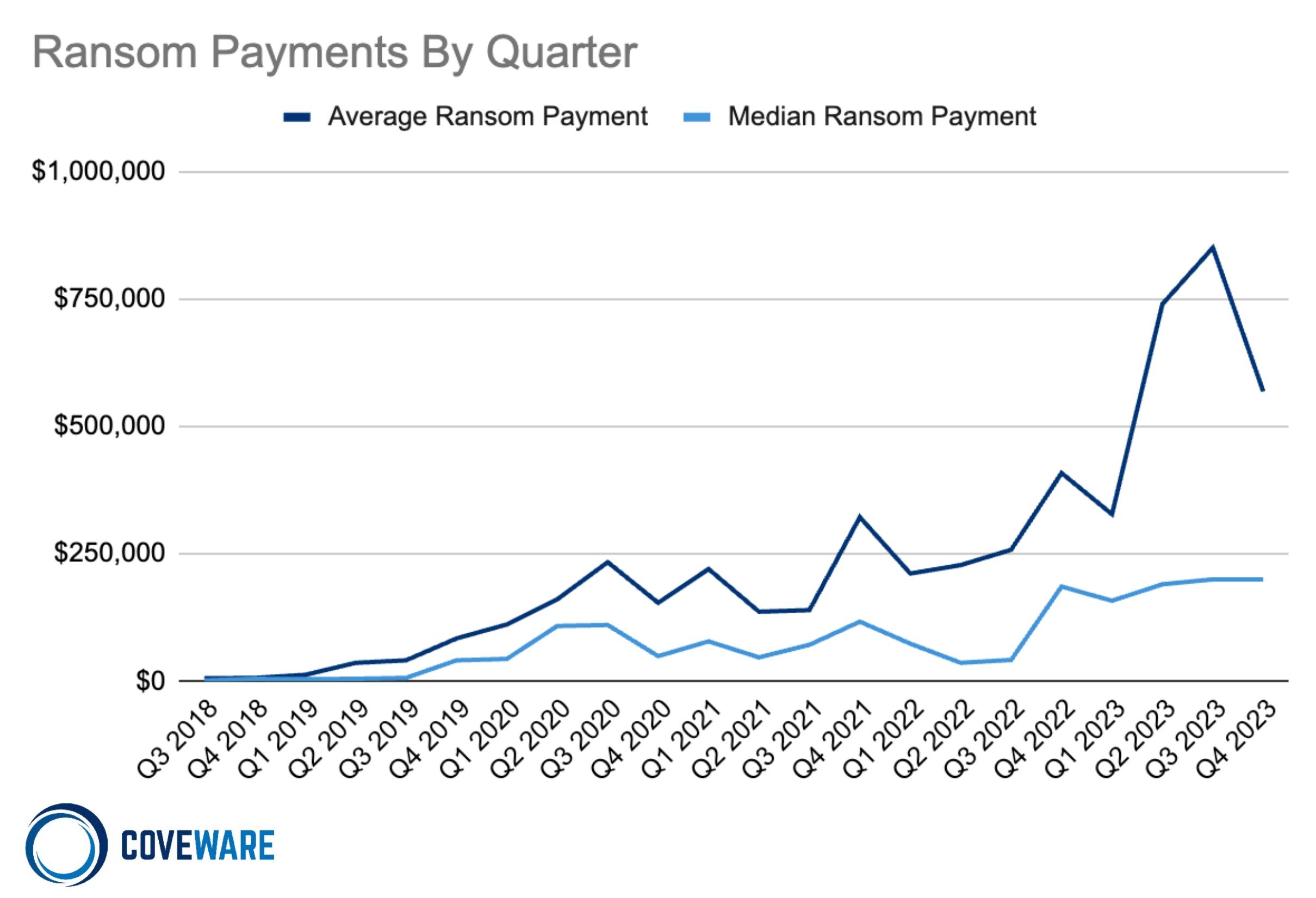

AVERAGE AND MEDIAN Ransom Payment Amounts in Q4 2023

Average Ransom Payment

-33% from Q3 2023

Median Ransom Payment

No Change from Q3 2023

In Q4, the average ransom payment decreased to $568,705 (-33% from Q3 2023), whereas the median ransom payment stabilized and remained at $200,000 (no change from Q3 2023). The trend aligned with a relative decline in the size of victims impacted (discussed further in this report), and a reappearance of small game actors groups who reclaimed some market share after previously dropping in frequency during Q3.

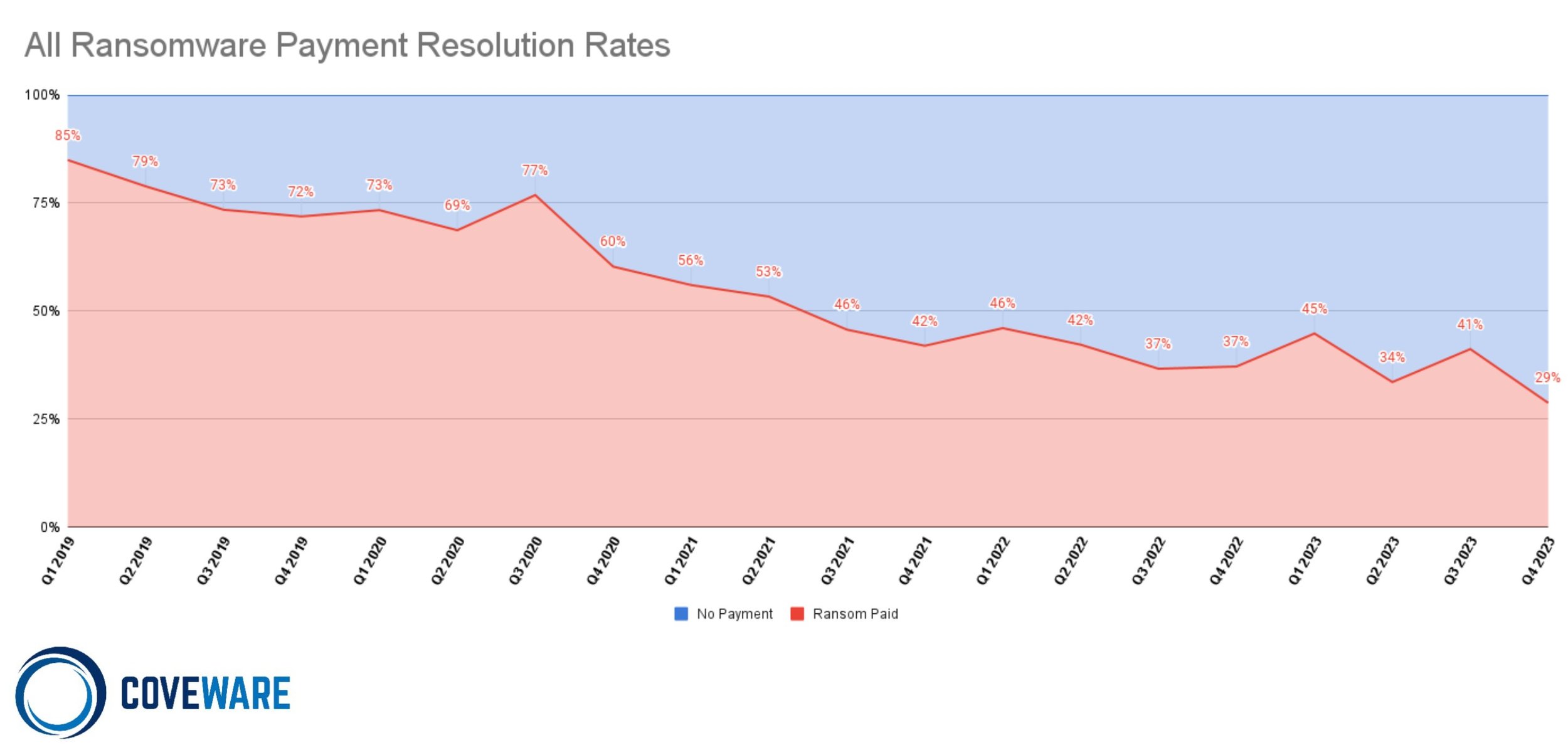

Ransom Payment Rate in Q4 2023

The proportion of ransomware victims that opted to pay ransoms in Q4 2023 dropped to a record low margin of 29%. This data point is driven by several variables: (1) Continued resiliency growth in enterprise environments; companies impacted by ransomware are increasingly able to recover from incidents partially or fully without the use of a decryption tool. (2) Data driven reluctance to pay for intangible promises from cybercriminals, such as the promise not to publish/misuse stolen data and the promise to exempt the company from future attacks or harassment; the industry continues to get smarter on what can and cannot be reasonably obtained with a ransom payment. This has led to better guidance to victims and fewer payments for intangible assurances.

Ransom Payment Rate for Data Exfiltration-Only Matters in Q4 2023

Echoing the sentiment above, we observed a decrease in the volume of data-exfiltration-only payments. Q4 was rife with examples of how data assurances can fail, even when interacting with well-known “brand established” ransomware groups. These cautionary tales have allowed us to offer timely and detailed examples to other companies of why threat actors cannot be trusted to prevent ongoing misuse/publication of stolen data, and why payments to them for these imaginary assurances have zero if not sub-zero value.

Most Common Ransomware Variants in Q4 2023

| Rank | Ransomware Type | Market Share % | Change in Ranking from Q3 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akira | 17% | - |

| 2 | BlackCat | 10% | - |

| 3 | Lockbit 3.0 | 8% | +1 |

| 4 | Play Ransomware | 6% | - |

| 5 | Silent Ransom | 5% | New in Top Variants |

| 5 | Medusa | 5% | New in Top Variants |

| 6 | NoEscape | 4% | New in Top Variants |

| 7 | Phobos | 4% | New in Top Variants |

Market Share of the Ransomware attacks

Akira carried over its lead from Q3 as the most active variant we responded to in Q4. While BlackCat attacks remained prevalent for the first part of the quarter, their activity materially diminished in December following the disruption and seizure of BlackCat infrastructure by law enforcement. Overall, Q4 was marked by a more diverse distribution of variants including smaller-enterprise-focused groups and non-affiliated lone wolf actors, whereas the Q3 market was notably cornered by only a few big game actors.

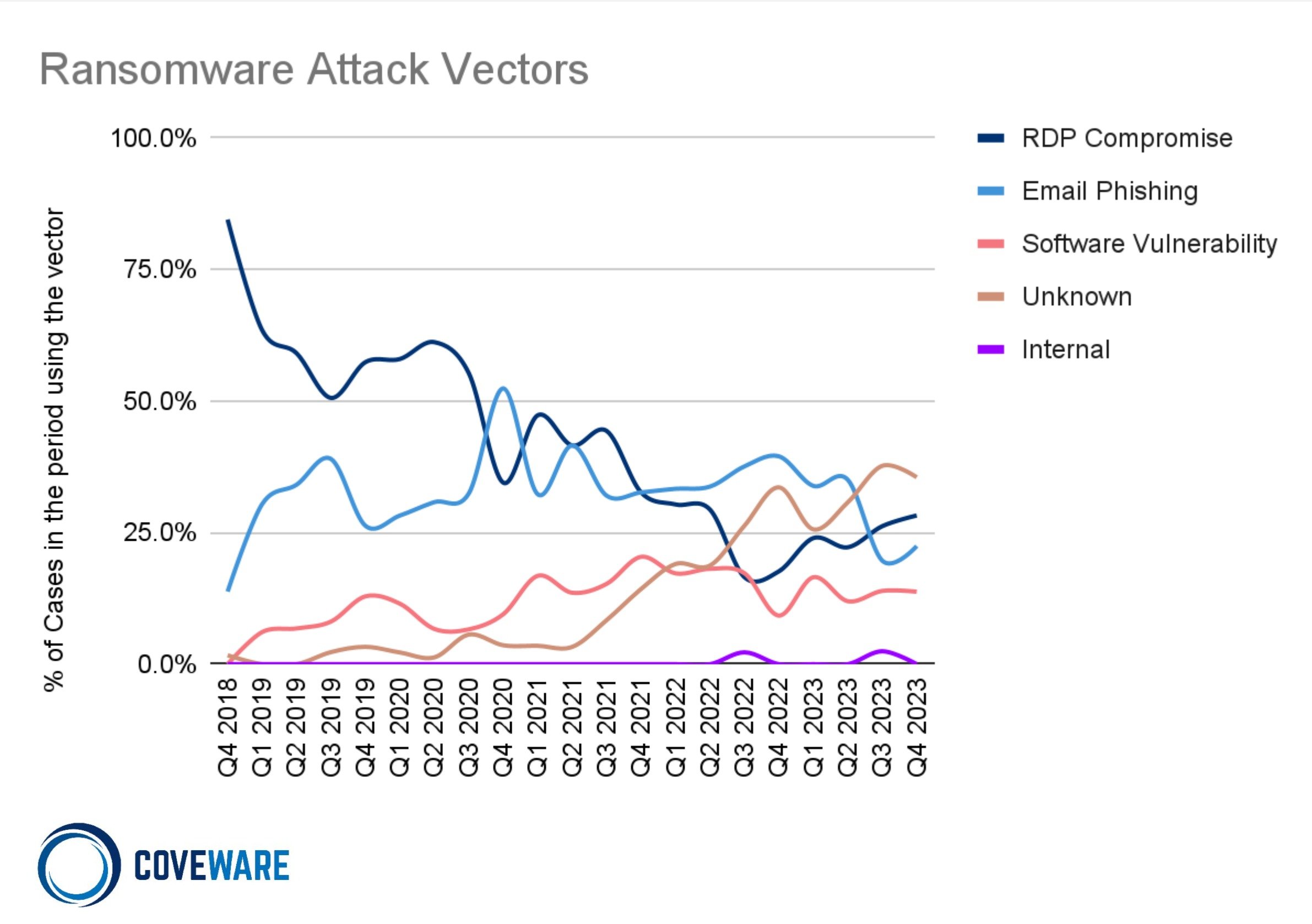

Most Common Attack Vectors and Tactics used by Ransomware Threat Actors in Q4 2023

Q4 attack vector trends demonstrated a traditional matrix of small-enterprise-focused actors leveraging basic ingress vectors such as brute force RDP attacks at the same time that mid-to-large-enterprise focused actors relied on CVE exploits and increasingly sophisticated social engineering, including SIM Swap attacks. Notably, the Cisco ASA vulnerability (CVE-2023-20269) was one of the most heavily documented ingress points, particularly among Akira ransomware attacks and particularly affecting software services companies and managed service providers. Threat actors who focused on the largest and most high profile entities relied on social engineering attacks directed at internal Help Desk staff (the goal being to gain control of high level IT personnel accounts by convincing the helpdesk to reset credentials controlled by the threat actor), as well as SIM Swap attacks against executives to gain control of SMS-based MFA authentication codes that can grant the bad actor access to other high value company resources. While the RDP/VPN and CVE attacks were most commonly associated with encryption-focused attacks, the phishing/social engineering approaches were most commonly associated with data-exfiltration-only attacks, where the scope of compromise was limited to email, OneDrive and Sharepoint resources as opposed to on-prem access to physical servers and endpoints.

Most Common TTPs used in Ransomware Attacks in Q4 2023

Impact [TA0040]: Impact consists of techniques used by adversaries to disrupt the availability or compromise the integrity of the business and operational processes. Techniques used for impact can include destroying or tampering with data. In some cases, business processes can look fine, but may have been altered to benefit the adversaries’ goals. These techniques might be used by adversaries to follow through on their end goal or to provide cover for a confidentiality breach. This TTP also includes tampering with credentials to deny access to virtual environments like ESXi. This is a very common tactic used by ransomware groups Akira, NoEscape and Rhysida.

Data Encrypted for Impact [T1486]: Encryption of files is the most common form of impact observed. This may include forensics logs and artifacts as well that may inhibit an investigation.

Data Destruction [T1485]: Most of the time, data destruction is aimed at the destruction of forensic artifacts via the use of SDelete or CCleaner. Unfortunately, sometimes ransomware actors destroy production data stores (sometimes malicious, sometimes by accident).

Service Stop [T1489]: Threat actors seek to stop or disable services on a system to render those services unavailable to legitimate users. Stopping critical services or processes can inhibit or stop response to an incident or aid in the actor’s overall objectives to cause damage to the environment.

Resource Hijacking [T1496]: Threat actors may leverage the resources of co-opted systems to complete resource-intensive tasks, which may impact system and/or hosted service availability.

Lateral Movement [TA0008]: Lateral Movement by threat actors consists of techniques used to enter and control remote systems on a network. Successful ransomware attacks require exploring the network to find key assets such as domain controllers, file share servers, databases, and continuity assets that are not properly segmented. Reaching these assets often involves pivoting through multiple systems and accounts to gain access. Adversaries might install their own remote access tools to accomplish Lateral Movement or use legitimate credentials with native network and operating system tools, which may be stealthier and harder to track. Favored tactics involve the exploitation of SMB/Windows Admin Shares, internal RDP, and RMM tools such as AnyDesk and ScreenConnect, though these remote access tools are not as popular for Lateral Movement as other purposes.The two most observed forms of lateral movement are:

Remote Services [T1021 and T1210], which is primarily the use of VNC (like TightVNC) to allow remote access or SMB/Windows Admin Shares. Admin Shares are an easy way to share/access tools and malware. These are hidden from users and are only accessible to Administrators. Threat actors using Cobalt Strike almost always place it in an Admin share. Usage of internal RDP remains one of the fastest and most efficient methods for lateral movement if a threat actor has the proper credentials.

Lateral Tool transfer [T1570]: Primarily correlates to the use of PSexec, which is a legitimate windows administrative tool. Threat actors leverage this tool to move laterally or to mass deploy malware across multiple machines.

Alternate Authentication Method: Pass the Hash [T1550.002]: Threat actors may use stolen application access tokens to bypass the typical authentication process and access restricted accounts, information, or services on remote systems. These tokens are typically stolen from users or services and used in lieu of login credentials.

Exfiltration [TA0010]: Exfiltration consists of techniques that threat actors may use to steal data from a network. Once data is internally staged, threat actors often package it to avoid detection while exfiltrating it from the bounds of a network. This can include compression and encryption. Techniques for getting data out of a target network typically include transferring stolen data over threat actor command and control channels. Common exfiltration tools used by threat actors include: Megasync, Rclone, Filezilla, Windows Secure Copy (WinSCP), Cloud User Agents (DropBox, OneDrive). Some actors have favored tools. For instance, Akira prefers WinSCP, while BlackCat and the Scattered Spider groups prefer Filezilla.

Exfiltration over Web Service [T1567] is the most common sub-tactic, which covers use of a variety of third party tools such as megasync, rclone, Filezilla or Windows Secure Copy.

Command and Control [TA0011]: Command and Control consists of techniques that adversaries may use to communicate with systems under their control within a victim network. Threat Actors (TAs) commonly attempt to mimic normal, expected traffic to avoid detection. TA’s will use legitimate software, leveraging trusted domains and signed executables, to maintain an interactive session on victim systems. When compared to post-exploitation channels that heavily rely on terminals, such as Cobalt Strike or Metasploit, the graphical user interface provided by RMMs are more user friendly. With the popularity of SaaS (Software as a Service) models, many RMMs are further offered as cloud-based services and by having command & control channels rely on legitimate cloud services, adversaries make attribution and disruption more complex.

Common tools they use are AnyDesk, TeamViewer, LogMeIn and TightVNC. ScreenConnect has been used heavily in Q3, more so than any other RMM. ScreenConnect has a ‘backstage mode’ feature, which allows for complete access to the Windows terminal and PowerShell without the logged-on user being aware, making it a particularly effective tool. There are many ways an adversary can establish command and control with various levels of stealth depending on the victim’s network structure and defenses:

Remote Access Software [T1219]: Ransomware threat actors will use legitimate software to maintain an interactive session on victim systems. Common tools observed in Q3 were ScreenConnect, AnyDesk, TeamViewer, LogMeIn, and TightVNC.

Ingress Tool Transfer [T1105]: Threat actors may transfer tools or other files from an external system into a compromised environment. Tools or files may be copied from an external adversary-controlled system to the victim network through the command and control channel or through alternate protocols such as FTP. Once present, adversaries may also transfer/spread tools between victim devices within a compromised environment (i.e. Lateral Tool Transfer).

Discovery [TA0007]: Threat actors use Discovery techniques to gain knowledge about a target’s internal network. These techniques help adversaries observe the environment and orient themselves before deciding how to navigate the network to achieve their impact objectives. Native operating system tools are often used toward this post-compromise information-gathering objective. The most observed tactics of discovery we observed in Q4 were:

Network Service Scanning (T1046): Primarily consists of abusing Advanced IP Scanners to identify what network hosts are available.

Process Discovery (T1057): Tools commonly abused are Process Explorer or Process Hacker, which allow threat actors to check active processes and kill them.

System Owner/User Discovery (T1033): A tactic used to get a listing of accounts on a system or network such as the use of ‘whoami’ command to identify the username from a system.

System Information Discovery [T1082]: Threat actors may attempt to get detailed information about the operating system and hardware, including version, patches, hotfixes, service packs, and architecture. Adversaries may use the information from System Information Discovery during automated discovery to shape follow-on behaviors, including whether or not the adversary fully infects the target and/or attempts specific actions.

File + Directory Discovery [T1083]: Actors may enumerate files and directories or may search in specific locations of a host or network share for certain information within a file system. Adversaries may use the information from File and Directory Discovery during automated discovery to shape follow-on behaviors, including whether or not the adversary fully infects the target and/or attempts specific actions.

Domain Trust Discovery [T1482]: Adversaries may attempt to gather information on domain trust relationships that may be used to identify lateral movement opportunities in Windows multi-domain/forest environments.

Victim size in Ransomware Attacks in Q4 2023

The median company size of victimized organizations fell to 231 employees (-32% from Q3 2023). The quarter was highlighted by several large incidents that drew media attention, along with regulatory reporting requirements that will likely lead to many more company’s having to publicly disclose incidents large and and small. Despite this, ransomware remains predominantly a small to mid market company problem.

Industry Distribution of Ransomware Victims in Q4 2023

Mirroring trends from Q3, the big four impacted industries remained static quarter over quarter: Professional Services, Healthcare, Consumer Services and Public Sector. As we’ve noted in past reporting, ransomware is, and has always been, an industry-agnostic crime and when a single vertical appears more in the data than its counterparts, it is almost always incorrect to characterize this as a “targeted” sector; a sector will appear more in the data if it has general characteristics that make it the low hanging fruit and the path of least resistance (i.e. small businesses and municipal offices that fall beneath the cybersecurity poverty line, tend to be behind on patching, and have strained ratios of IT personnel to number of servers/endpoints to maintain).

A much more telling predictor of which threat actor group your organization is most likely to fall victim to is company size and reported revenue figures. Some threat groups may still fall into the “we’ll take what we can get” category, but our data suggests that others are decidedly more particular about victim attributes and exclusively target enterprises over a certain size/financial threshold.